“Enjoy your trip!” said the smileless lady who issued my 200 Baht ticket to enter Thailand’s House of Opium opposite the Anantara Golden Triangle Elephant Camp & Resort in Bang Sop Ruak village near Chiang Saen, north Thailand, 500 miles north of Bangkok on the border of Myanmar and Laos.

The area still accounts for a large per cent of world’s opium production. As much as 900 tons of “Tar” or “Yen Shee Suey” a year.

Thailand’s late beloved Princess Mother Mae Fah Luang (“Royal Mother From The Sky”) wanted to help end the local hill tribes’ dependence on growing poppies for the drug trade. So, she had the land re-planted with substitute cash crops and built a huge, three-floor museum and 50-acre “educational culture park” dedicated to poppy tears and the power of flowers.

Maybe I was expecting too much. Perhaps I built up the mind-expanding experience too greatly, the illuminating changes that visiting the museum would bring about in my consciousness and my perception of the nature of reality too much. I expected to suddenly feel and understand everything that was happening everywhere in the universe and really get inside “the isness of things”, appreciating them not for their uses but for what they really are.

After all, travel should cleanse the doors of perception now and then, freshen our outlook and give us a new perspective on life, a new alternate lens through which to view the world. Without any increase in pupil size.

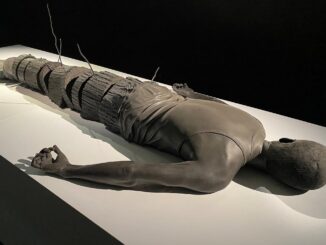

I walked up a dark 137-metre-long tunnel. On the walls around me tortured souls – the carved faces of addicts who were amusing themselves to death – screamed noiselessly. Below me, river pulsed and breathed and eddied, taking me to the intersection of profound mystical experience and psychological discovery.

The ceiling rippled and glowed as I walked into a field of artificial flowers and the history of psycho-active opiods. I experienced a sense of infinity as all the rooms were huge. And no one else was there.

I walked on, preparing my ego to be annihilated and to transcend my self-conscious selfhood. I was still the only one there and I was beginning to feel ripped off. Glucose was still reaching my brain and I felt lucidly bored. I OD-ed on papaver sominfera trivia. The walls bent around me. Sending me confused messages which I struggled to assimilate.

I experienced absolutely no change of consciousness for the next five minutes (which felt like a lifetime) as I absorbed multi-media information about the power of the poppy and hallucinative properties of the dream flower, “God’s natural medicine”.

I came to an oriental tea house in Yaowaret, learning how the British paid the Chinese with opium for their tea. I was transported to old Siam. My £5 trip took me past a British tea clipper, through India, Tasmania, Afghanistan and other centres of production. Even to Switzerland. I passed tall cabinet after tall cabinet of bongs and opium pipes with replica opium balls. Smoked spiraled around as I drowsily read that in the 1870s 9,600 cases of 72kgs were processed at Calcutta auctions every year. In a fact-induced trance, I read about Jardine and Matheson, the Edinburgh dealers and the East India Company’s monopoly.

I then found myself reading about the surrender of drug warlord Khun Sa’s Mong Tai Army in 1996, favoured channels of money laundering and the CIA’s involvement in the Golden Triangle’s opium farms. Having probably taken the wrong turning, again gone the wrong way or gone up the stairs at the wrong time as drugs are disorientating things, I learned that between 400 and 1,200 Arab traders introduced opium to China. And to India by 700.

How the Arabs relied on opium and mandrake as surgical anaesthetics. And, due to the constipation often produced by the consumption of opium, it was one of the most effective treatments for cholera, dysentery and diarrhoea. And was once a trusted cough suppressant for children and distributed among soldiers in the American Civil War.

In neurasthenic, neuralgic detail, room after room, I learned that the Ottoman Empire supplied the west with opium long before China and India. How Coleridge, who co-wrote “Kubla Khan”, was first prescribed it for rheumatic fever. That tobacco mixed with opium was called “madak. I read all about the Opium Wars and how opium became the most single valuable commodity trade and is the oldest systematic international crime, smuggling providing at one time 20 per cent of the revenue of the entire British Empire. And how Mao blamed opium and the British for everything. And how, by 1906, China was producing 85 percent of the world’s opium, some 35,000 tons, and 27 per cent of its adult male population were regularly shit-faced and out of it with 13.5 million junkies consuming 39,000 tons of opium yearly.

I read on about the California Pharmacy and Poison Act in 1907, making it a crime to sell opiates without a prescription. About opium addiction among the Aborigine people, its criminalization, the Rolleston Act in Britain in 1926 through which doctors were allowed to prescribe opiates if they believed their patients demonstrated a medical need. There wasn’t too much, if anything, on palliative care.

Now I know Sertuner first isolated morphine in 1804 and sales began in 1827. And that codeine was isolated in 1832 and heroin first synthesized in 1874. Pleasurable facts like that. I was euphoric by the end of it all. I had enough “Skee” and “Easing Powder” for the day. My head throbbed with “Midnight Oil” and Chinese molasses.

The trip came to a close in the museum’s Gallery of Excess with photos of smuggling methods (from teddy bears and stomach bags) and naming and shaming victims of the “demon drug” like President Benjamin Franklin, Jimi Hendrix, John Belushi, Kurt Cobain and Bela “Count Dracula” Lugosi.

Then I journeyed into the Hall of Reflection and the works of the visionary Prince Mother, honoured as a “great personality in public service in the fields of education, applied science and environmental development”. As well as social entrepreneurship.

When I left the building there was smoke scrolling up into the sky. They were burning the land, readying it for its yearly sowing.

For more information on the House of Opium, please visit their website: https://houseofopium.co.

Author Bio:

Kevin Pilley is a former professional cricketer and chief staff writer of PUNCH magazine. His humour, travel, food and drink work appears worldwide and he has been published in over 800 titles.

Photographs copyright of the Tourism Authority of Thailand

Be the first to comment